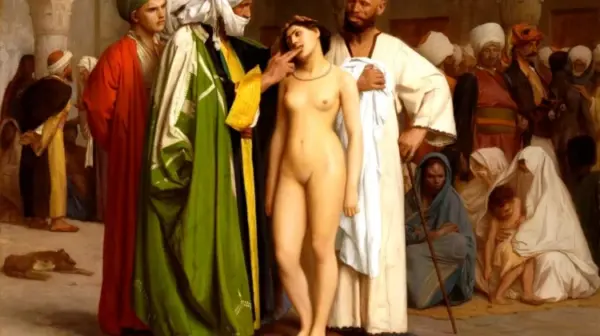

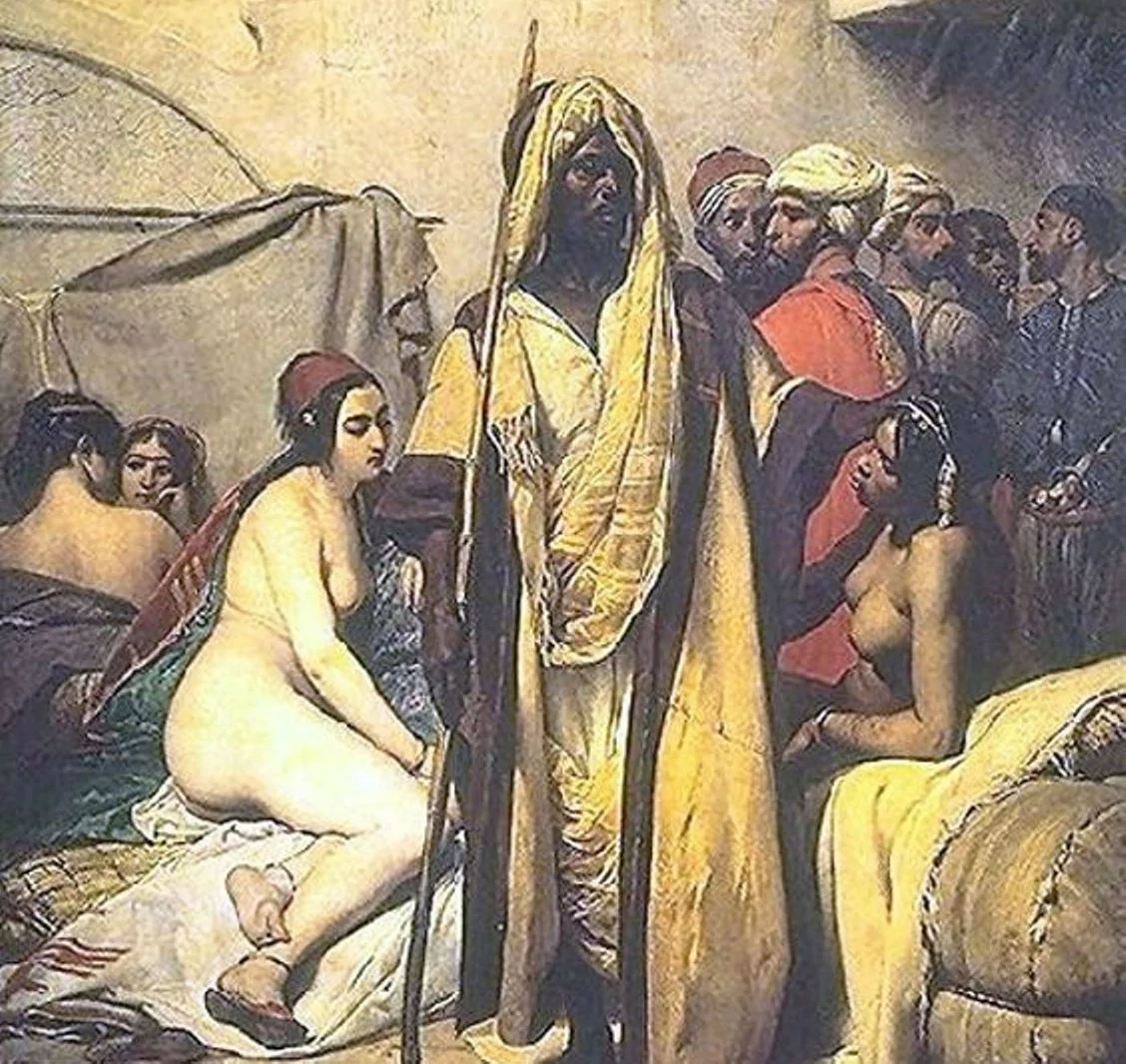

Prošle godine, politička stranka u Njemačkoj izazvala je kontroverzu kada je koristila sljedeću sliku u svojoj izbornoj kampanji kako bi ilustrirala jedan od razloga protiv imigracije.

Prošle godine, politička stranka u Njemačkoj izazvala je kontroverzu kada je koristila sljedeću sliku u svojoj izbornoj kampanji kako bi ilustrirala jedan od razloga protiv imigracije.

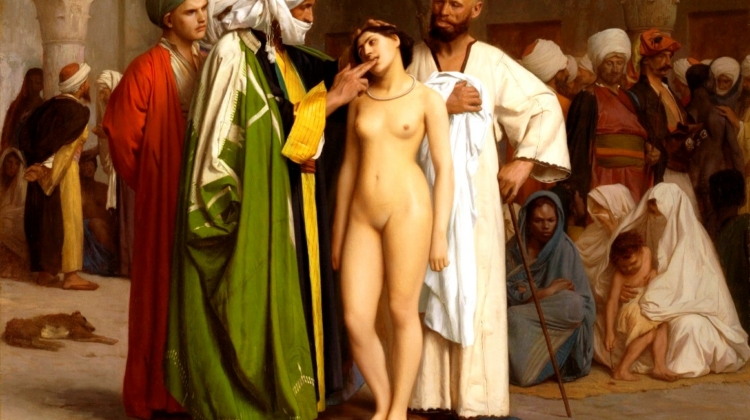

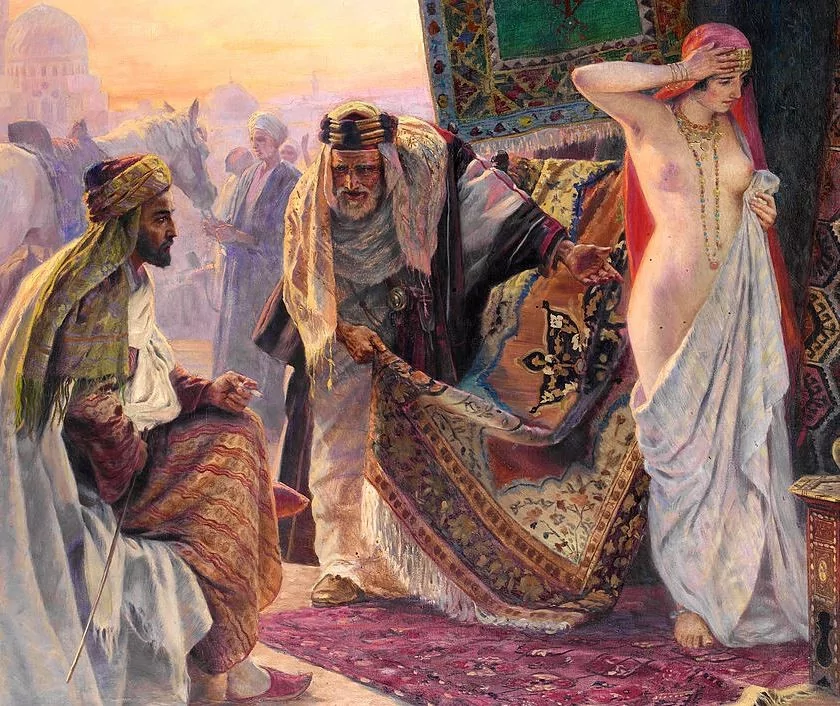

Naslikana u Francuskoj 1866. godine pod nazivom “Tržište robova”, slika je opisana kao “prikaz crnog, očito muslimanskog trgovca robljem koji pokazuje golu mladu ženu svjetlije kože grupi muškaraca na pregled”, vjerojatno u Sjevernoj Africi.

Stranka Alternativa za Njemačku (AfD) postavila je nekoliko plakata s ovom slikom s sloganom “Da se Europa ne pretvori u Eurabiju”. Mnogi s obje strane Atlantika bili su “potaknuti” ovom upotrebom; čak je i američki muzej gdje se nalazi originalna slika poslao pismo AfD-u “inzistirajući da prestanu koristiti ovu sliku” (iako je u javnom vlasništvu).

Objektivno govoreći, spomenuta slika “Tržište robova” prikazuje stvarnost koja se odvijala bezbroj puta kroz stoljeća: afrički, azijski i bliskoistočni muslimani dugo su ciljali europske žene – toliko da su ih milijuni bili zarobljeni tijekom stoljeća (vidi “Mač i scimitar” za obilan dokument).

Srećom, postoji još nešto – drugo sredstvo osim pisanja – koje dokumentira tu stvarnost: bezbrojne slike osim one koja se spominje o otmici, krijumčarenju i seksualnom ropstvu europskih žena; sve to dodatno naglašava opće prisutnost i notornost ovog fenomena. Uistinu, ovo je bila tako dobro poznata tema da su mnogi umjetnici iz devetnaestog i početka dvadesetog stoljeća specijalizirali za nju, često na temelju vlastitih očevica. (Kako jedna galerija umjetnosti navodi: “Mnogi … najvažniji slikari sami su putovali [u muslimanski svijet], a ono što su slikali temeljilo se na skicama koje su napravili dok su bili tamo …”)

U nastavku su samo 20 takvih slika (ih ima mnogo više). Osim što bilježim ime umjetnika, godinu slikanja i, gdje je moguće, naslov – informacije koje su često teško utvrditi – ograničio sam svoje primjedbe na važne digresije i pojašnjenja, uglavnom u prvih nekoliko slika, ostavljajući ostatak da govore sami za sebe. Slijede.

Islam’s Sexual Enslavement of White Women

Raymond Ibrahim, author of Sword and Scimitar, is a Shillman Fellow at the David Horowitz Freedom Center.

Last year, a political party in Germany provoked controversy when it used the following painting in its election campaign to illustrate one of the reasons it was against immigration.

Painted in France in 1866 and titled “Slave Market,” the painting was described as “show[ing] a black, apparently Muslim slave trader displaying a naked young woman with much lighter skin to a group of men for examination,” probably in North Africa.

The Alternative for Germany party (AfD) put up several posters of this painting with the slogan, “So that Europe won’t become Eurabia.” Many on both sides of the Atlantic were “triggered” by this usage; even the American museum where the original painting is housed sent AfD a letter “insisting that they cease and desist in using this painting” (even though it is in the public domain).

Objectively speaking, the “Slave Market” painting in question portrays a reality that has played out countless times over the centuries: African, Asiatic, and Middle Eastern Muslims have long targeted European women—so much so as to have enslaved millions of them over the centuries (see Sword and Scimitar for copious documentation).

As it happens, there is something else—another medium besides writing—that documents this reality: countless more paintings than the one in question concerning the abduction, trafficking, and sexual enslavement of European women; altogether they further underscore the ubiquity and notoriety of this phenomenon. Indeed, this was such a well-known theme that many nineteenth and early twentieth century artists and painters specialized in it, often based on their own eye-witness accounts. (As one art gallery puts it, “Many … of the most important painters did travel [to the Muslim world] themselves, and what they painted was based on the sketches they had made while they were there…)

Below are just 20 such paintings (there are many more). Aside from noting the artist’s name, year of painting, and, where possible, title—information which is often difficult to ascertain—I’ve limited my remarks to important asides and clarifications, mostly in the first few paintings, leaving the rest to speak for themselves. They follow.

“The Bulgarian Martyresses,” Konstantin Makovsky, 1877. Sliku je napravio Konstantin Makovsky 1877. godine. Ona prikazuje događaje iz prethodne godine, kada su osmanski neregularni vojnici (tzv. bašibozuci ili “ludi glave”) silovali i masakrirali kršćanske žene Bugarske i njihovu djecu. Američki novinar MacGahan, koji je izvještavao iz Bugarske, napisao je sljedeće o tom incidentu: “Kada musliman ubije određeni broj nevjernika, siguran je u Raj, bez obzira na svoje grijehe…[O]bican musliman shvaća precept u širem značenju i broji i žene i djecu…bašibozuci, kako bi povećali broj, razrezali su trudne žene i ubili nerođene bebe.”

“The Bulgarian Martyresses,” by Konstantin Makovsky, 1877. It depicts events from a year earlier, when Ottoman irregular soldiers (the so-called bashi-bazouks or “crazy heads”) raped and massacred the Christian women of Bulgaria and their children. American journalist MacGahan, who reported from Bulgaria, wrote the following of this incident: “When a Mohammedan has killed a certain number of infidels he is sure of Paradise, no matter what his sins may be.…[T]he ordinary Mussulman takes the precept in broader acceptation, and counts women and children as well…. the Bashi-Bazouks, in order to swell the count, ripped open pregnant women, and killed the unborn infants.”

“The Abduction of a Herzegovinian Woman,” Jaroslav Čermák, 1861. Sliku je napravio Jaroslav Čermák 1861. godine. Prema službenom opisu muzeja: “Uznemirujuća i izuzetno evokativna, prikazuje bijelu, golu [i trudnu?] kršćansku ženu kako je otete iz svog sela od strane osmanskih plaćenika koji su ubili njenog supruga i dijete.”

“The Abduction of a Herzegovinian Woman,” by Jaroslav Čermák, 1861. From the museum’s official description: “Disturbing and extremely evocative, it depicts a white, nude [and pregnant?] Christian woman being abducted from her village by the Ottoman mercenaries who have killed her husband and baby.”

“Otmica”, Eduard Ansen-Hofmann (1820.-1904.).

“The Slave Market, Tržnica robljem” by Otto Pilny, 1910.

“Abducted,(Oteti)” by Eduard Ansen-Hofmann (1820–1904).

“Namona,” by Henri Tanoux, 1883.

“”Gorka čaša ropstva”,The Bitter Draught of Slavery,” by Ernest Norman, 1885.

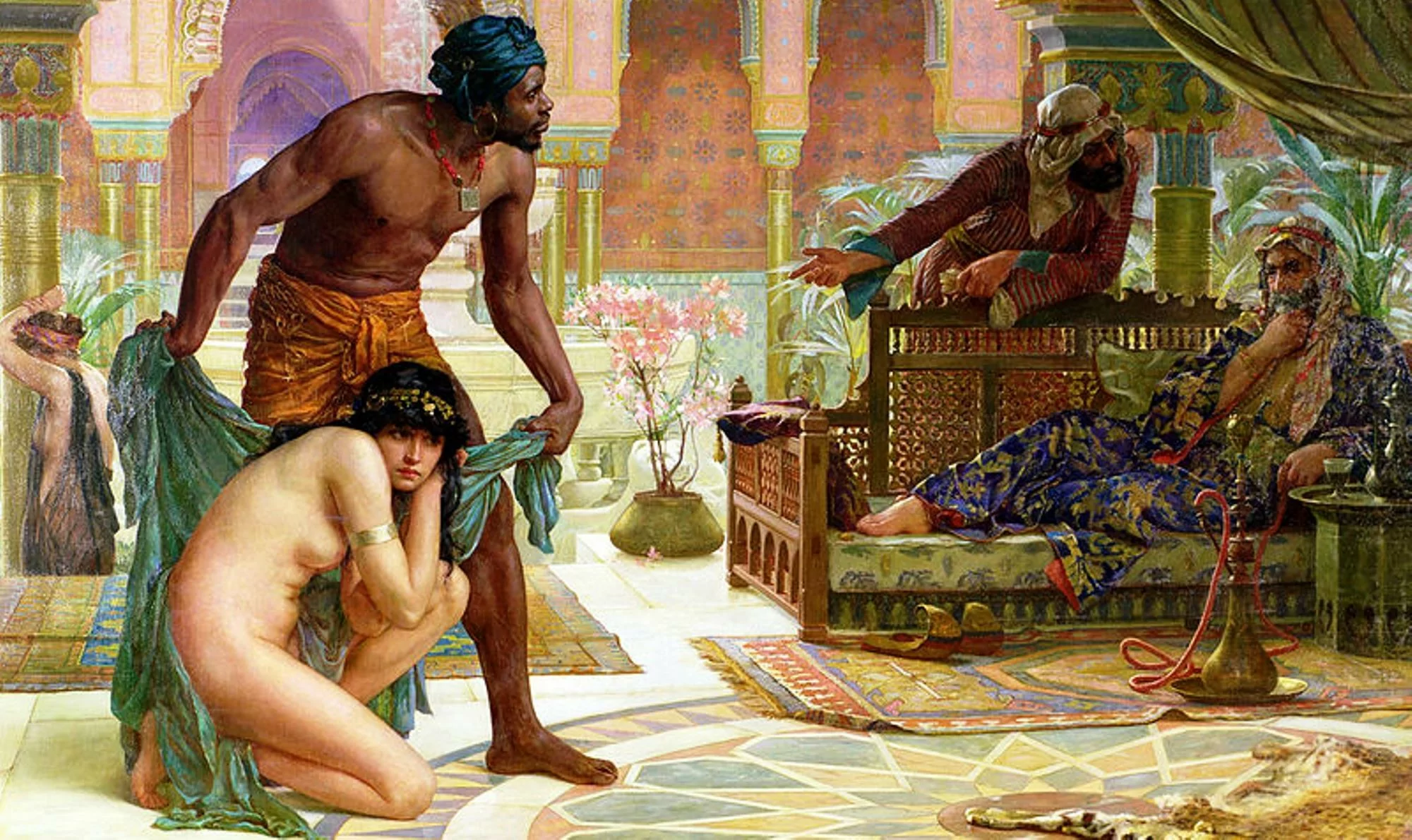

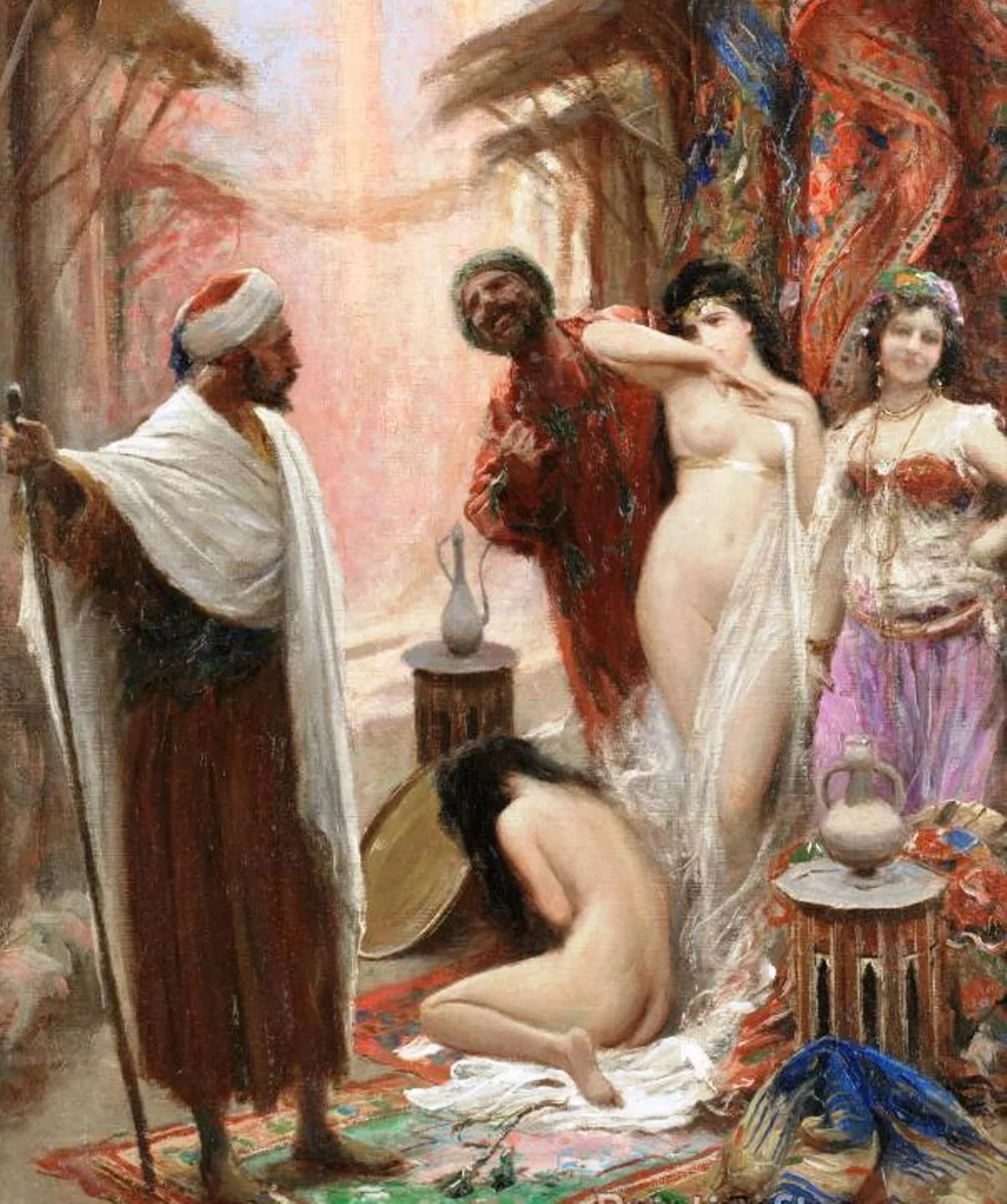

“Nova isporuka, A New Arrival,” by Giulio Rosati (1858–1917).

“Nova ropkinja, The New Slave Girl,” by Eduard Ansen-Hofmann (1820-1904).

“Odabir ropkinja, Examining Slaves,” by Ettore Cercone, 1890.

“Diler robova, Slave Dealer,” by Otto Pilny, 1919.

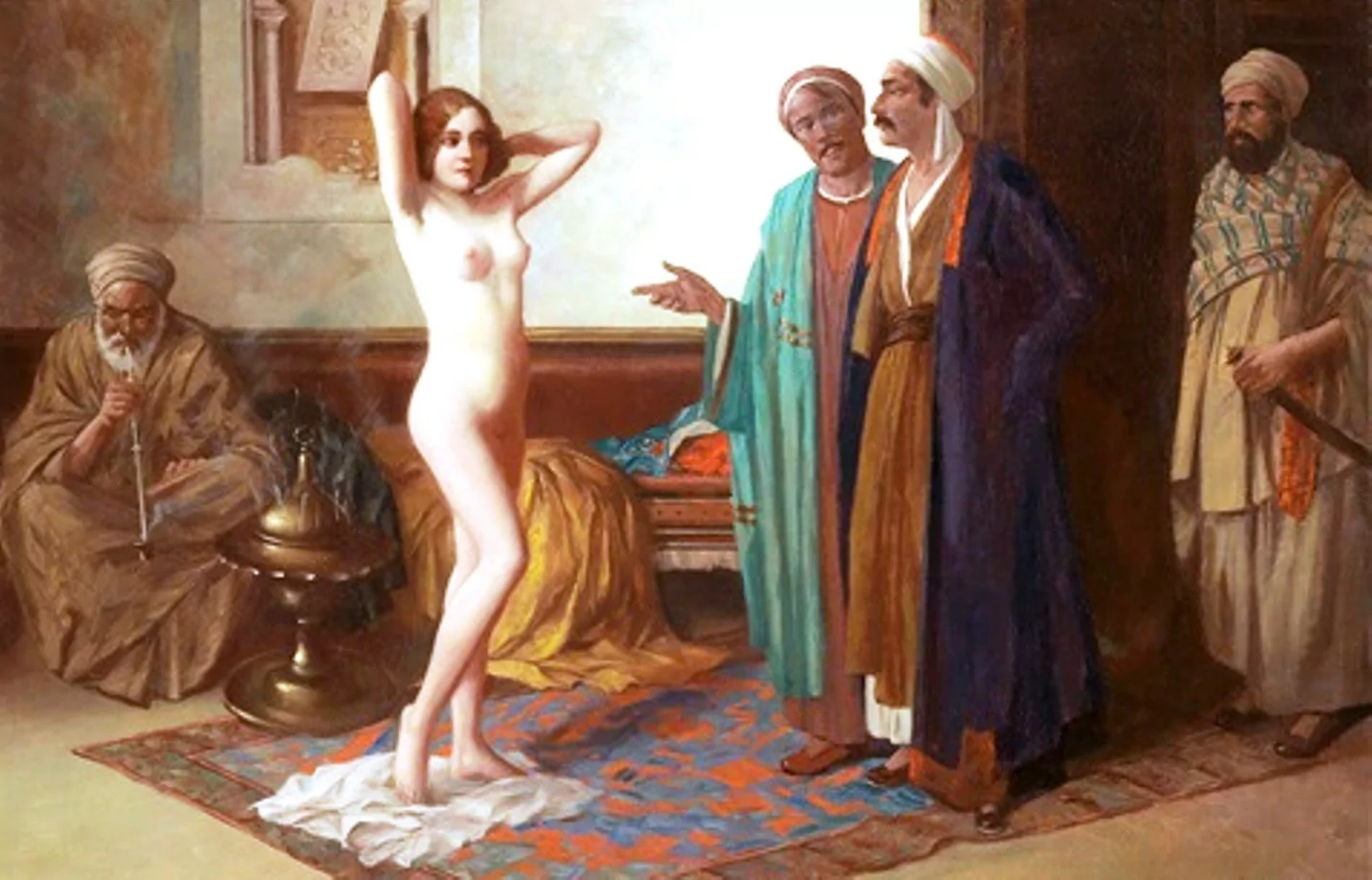

“Slave Market,” by Eduard Ansen-Hofmann, 1900.

“Cijenkanje, Slave Trade Negotiations,” by Fabio Fabbi (1861-1946).

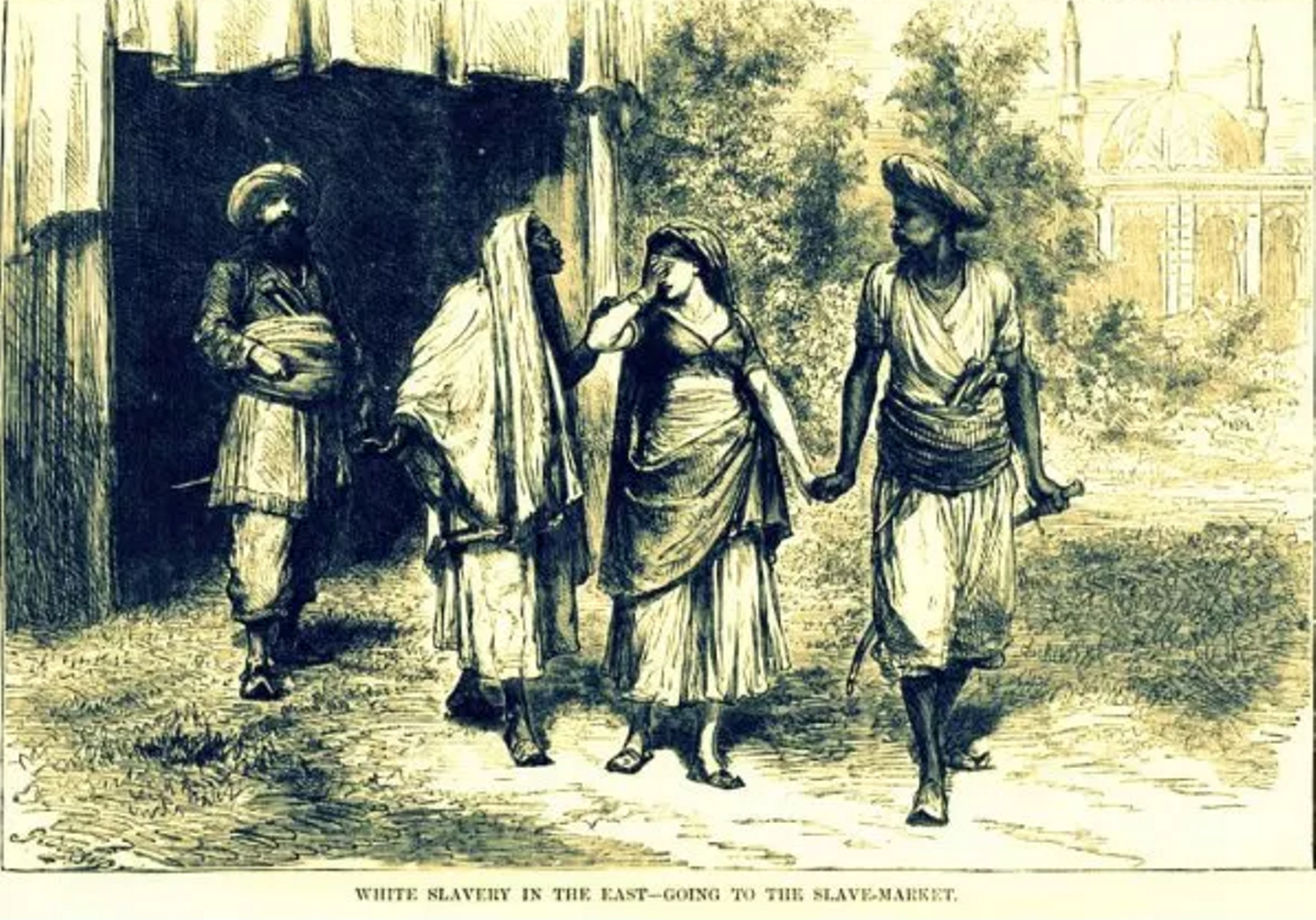

“Bijelkinje na istoku vode na tržnicu robova, White Slavery in the East—Going to the Slave Market,” by Harper’s Weekly, April 1875.

“Bijelkinje na istoku vode na tržnicu robova, White Slavery in the East—Going to the Slave Market,” by Harper’s Weekly, April 1875.

“Pridošlica, New Arrival,” by Eduard Ansen-Hofmann (1820-1904).

“Srpska konkubina, The Serbian Concubine,” by Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, 1876.

“Slave Market,” by Émile Jean-Horace Vernet, 1836.

“Slave Market,” by Jean-Leon Gerome, 1871.

“Harem Captive,” by Eisenhut Ferencz, 1903.

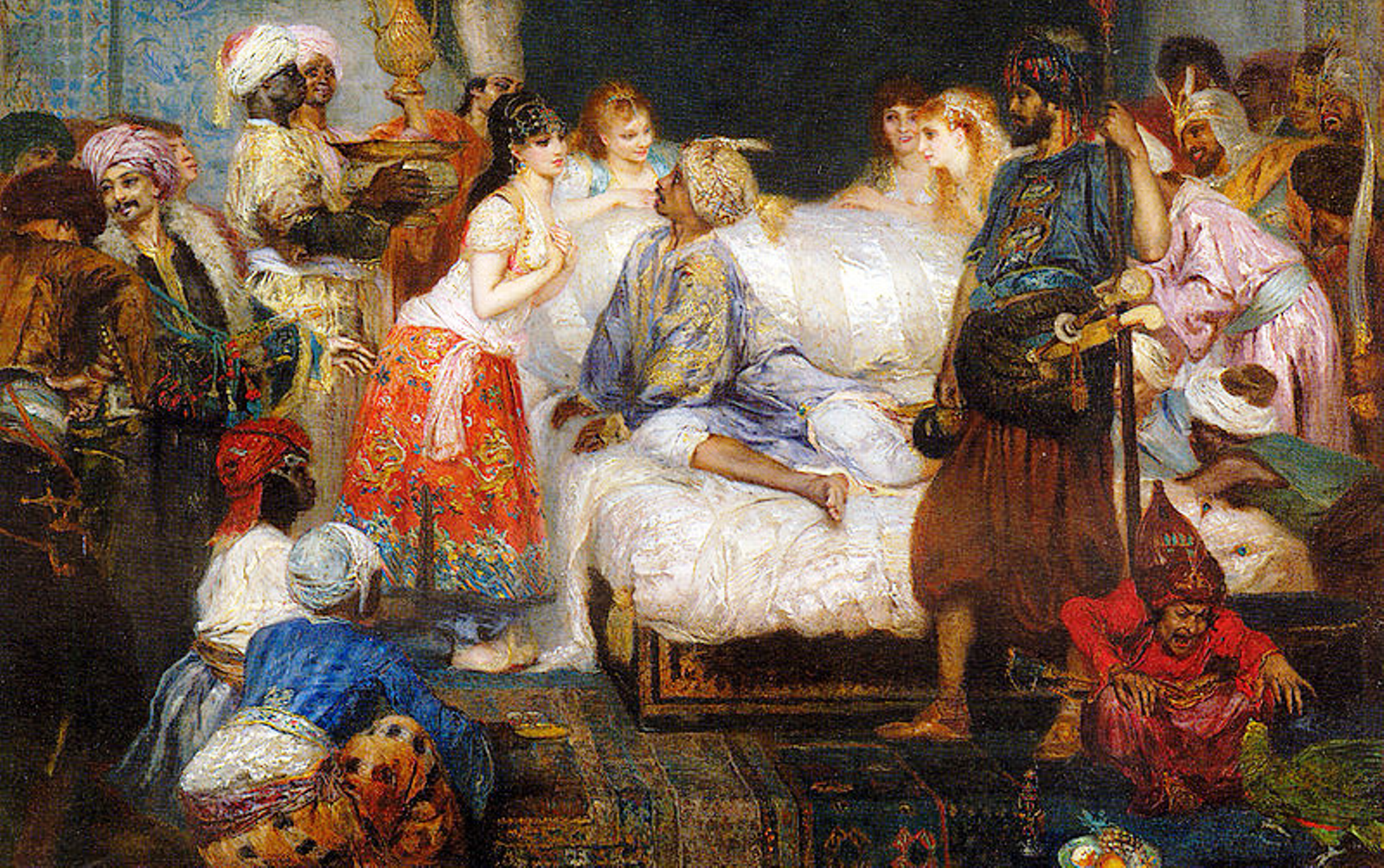

“Scene from the Harem,” by Fernand Cormon, 1877.