Our enemy is a radical network of terrorism, and every government that supports them. . . . From this day forward, any nation that continues to harbor or support terrorism will be regarded by the United States as a hostile regime.

by US President George W. Bush

Over the past decade of conflict in the Balkans, the United States has repeat- edly backed radical extremists in southeastern Europe whose activities and ideals have little in common with those of the West. This pattern of cooperating with dubious individuals and shadowy groups to achieve short-term U.S. policy goals of questionable logic, merit, or morality has been in evidence since the Bosnian conflict of the early 1990s through to the more recent Kosovo and Macedonian conflicts.

The 11 September 2001 attacks on New York’s World Trade Center and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., however, should now force us to reexamine U.S. policy in the Balkans, for two reasons. First, important elements of Osama bin Laden’s organization, al Qaeda, as well as other Islamic extremist organizations have been operating in the region for the better part of a decade. Consequently, any comprehensive policy to combat international terrorism must involve southeastern Europe.

Second, a thorough examination of bin Laden’s alliances in the Balkans also reveals a disturbing pattern-ironically, for much of the past decade, bin Laden and the United States have often found themselves supporting the same factions in the Balkan conflicts. Moreover, even as the United States has become more deeply engaged in the region, bin Laden has been expanding his network of operatives in southeastern Europe, right under the very noses of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the United States.

Recognizing this irony provides many explanations for the failures of American policy in the region.

The Dimensions of the Problem

Much speculation has recently circulated in Western media on bin Laden’s ties to the Balkans.

Often it is claimed that religious extremists are on the verge of creating Islamic republics throughout the southern Balkans or that the region has become the main base for attacks on the West.

This is too simplistic an understanding, however, of the way in which al Qaeda or other terrorist organizations operate; for instance, we now know that the al Qaeda organization has been successfully based in Western countries such as Germany for years.1

Three caveats should be kept in mind when trying to understand the potential threat posed by bin Laden or similar Islamic extremists operating in southeastern Europe.

First, Muslim populations in the Balkans are on the whole relatively secular in their orientation, at least in comparison to Muslim populations in such states as Egypt, Pakistan, or Saudi Arabia.

For the vast majority of southeastern Europe’s 7 to 8 million Muslims, bin Laden’s variant of extremist Islam, generally known as Wahhabism, is of little interest or attraction.2

For the overwhelming majority of Albanians in Albania proper, Kosovo, or the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, for instance, recent political mobilization has not been motivated by a desire to create an Islamic theocratic state. Rather, as an old saying among Albanians goes, “The religion of Albanians is Albanianism.”

Similarly, for most Bosniaks, the connection with Islam is more a matter of ethnic identity than a strong religious orientation.3

Thus, there is little reason to believe that bin Laden or other Islamic fanatics can succeed in fomenting Islamic revolutions in the Balkans à la Iran or Afghanistan.

A second factor limiting the threat posed by Islamic extremists in the Balkans is the existence of an active, secularly oriented civil society among the native Muslim inhabitants in the region.

Secular Muslim intellectuals and nongovernmental organizations in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo enjoy a public prominence their colleagues in the more tightly controlled societies of the Middle East can only dream of.

In Bosnia, for instance, independent publications such as the Sarajevo newsweekly Dani or the daily newspaper Oslobodjenje have long been harsh critics of Alija Izetbegovic’s ties to bin Laden and other Islamic extremist organizations.

The third factor limiting the threat posed by bin Laden and other extremists is the fact that much of the southern Balkans is now under virtual NATO and United Nations occupation.

Given the fact that both Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo (and, perhaps, Macedonia in the not too distant future) have become de facto NATO protectorates, there are severe constraints regarding the extent to which radical extremists can operate in these areas as long as NATO is willing to exercise its powers and responsibilities.

In sum, there is little danger that bin Laden or like-minded fanatics can foment Khomeini-style Islamic revolutions in the Balkans or that they will be able to win over significant segments of the indigenous Muslim populations. Rather, the danger such extremists pose stems from their ability to organize and finance small groups of radicals intent on provoking general instability or inciting terror.

Over the past decade, al Qaeda and other radi- cal Islamic organizations have done this by forging ties with a handful of indigenous Muslim activists, such as former Bosniac president Izetbegovic, or radical groups such as the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), which are driven less by religious zealotry than by the simple desire to profit through drug smuggling or trafficking in human beings. What is unfortunate is that U.S. policy makers have often made common cause with such individuals and organizations.

__nation given the large number of individuals in Bosnia who are of Muslim background but are athe- ists and consequently prefer to use a term that does not have religious connotations.

The U.S. dalliance with Islamic extremists in the Balkans can be traced back to Bosnia in the early 1990s, when the United States provided covert support in the form of arms, training, and intelligence to forces commanded by Izetbegovic, the Bosniacs’ wartime leader. Prior to assuming the presi- dency of Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1990, Izetbegovic had been best known for his activities as an Islamic dissident who had been jailed on two occasions in the former Yugoslavia. Izetbegovic spent much of the 1970s and 1980s forging links with other Islamic movements, such as those affiliated with the Ayatollah Khomeini in Iran.4 In his most famous political manifesto, the 1970 Islamic Declaration, Izetbegovic had declared:

There is no peace or co-existence between Islamic faith and non-Islamic social and political institutions. . . . Our means are personal example, the book, and the word. When will force be added to these means? The choice of this moment is always a concrete question and depends on a variety of factors. However, one general rule can be postulated: the Islamic movement can and may move to take power once it is morally and numerically strong enough, not only to destroy the existing non-Islamic government, but to build a new Islamic government.5

In 1991, as war broke out in the former Yugoslavia, Izetbegovic invited fighters from Islamic countries to join the battle against Croats and Serbs. These fighters, known locally as mujahedin and believed to have numbered anywhere up to seven thousand strong, came from a variety of Islamic countries, including Afghanistan, Algeria, Egypt, Iran, and Jordan.

The mujahedin were mainly grouped within an ethno-religious unit named the 7th Muslim Brigade formed within the main structure of Izetbegovic’s army. The 7th Muslim Brigade’s area of operation was the heavily forested hill country of central Bosnia, and during the war the unit was accused of some of the most egregious war crimes committed by forces under Izetbegovic’s command. Investigations into these atrocities culminated in August 2001 with the indictment by the International Criminal Tribunal for the For- mer Yugoslavia (ICTY) of two Bosnian Muslim officers with command responsibility over the unit.6

Support for the Izetbegovic regime from Islamic extremist movements came in other forms, as well. One example of such support was the Third World Relief Agency (TWRA), run by a Sudanese national with ties to Sheik Omar Abdel Rahman, convicted of masterminding the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center. TWRA was reported to have raised up to $350 million from Islamic countries and other sources between 1992 and 1995 to support the Bosniacs’ war effort.7

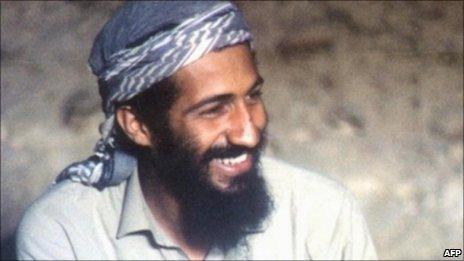

Osama bin Laden was a prominent supporter of the Izetbegovic regime, and bin Laden apparently benefited significantly from the relationship.

In 1993, Izetbegovic’s colleagues had provided Bosnian passports to bin Laden and several of his associates.8 According to one report, bin Laden himself visited Sarajevo in 1993 and showed off his passport to foreign reporters.9 Bosniak officials continued to issue passports to members of bin Laden’s organization as late as 1997.

It is clear that bin Laden and his associates used these Bosnian passports to help build their organization into the international terror network it has now become.

On 17 September 1999, for instance, Turkish secret police arrested a known bin Laden associate, Mahrez Amduni, who was traveling on a Bosnian passport. Amduni was at the time described as bin Laden’s top aide.

Thanks to these connections, by the mid–1990s Bosnia had become an important staging ground for Islamic militants organizing attacks on the West and/or Western targets. For instance, in February 1996, NATO troops in Bosnia raided a terrorist training camp outside the central Bosnian town of Fojnica. Among the items confiscated in the attack were an arsenal of weapons, the plans to several NATO installations in Bosnia, and, most dis- turbingly, booby-trapped children’s toys.

After the Bosnian war, several mujahedin who had fought in Bosnia continued their struggle in other parts of the world, including Kosovo, Chechnya, Western Europe, and the United States. Among them were Ahmet Ressemi, arrested on 14 December 1999 on the U.S.-Canadian border in a car carrying nitroglycerin and other bomb making materials. Ressemi was thought to be part of the foiled millenium bombing plot intended for Los Angeles International Airport. Several individuals arrested for the 1996 attack on the Khobar Towers building in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, which resulted in the deaths of nineteen U.S. military personnel, also confessed to having served with Bosniac military forces,12 and in 1999, the Central Intel- ligence Agency uncovered three plots by Bosnia-based Islamic extremists to attack a variety of targets in Western Europe.13

Bin Laden’s continued ties to Bosnia were evident as recently as July 2001, when three of his associates were arrested, under strong U.S. pres- sure, by Bosnian police in a Sarajevo suburb.14 More arrests of suspected terrorists followed in the wake of the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.15 Members of bin Laden’s organization apparently still con- sider Bosnia a safe haven of sorts; Bosnian interior minister Muhamed Besic recently claimed that up to seventy members of al Qaeda were attempting to flee Afghanistan for Bosnia in anticipation of U.S. strikes on bin Laden’s main refuge.16

Albania and Kosovo

During the Bosnian conflict, bin Laden also began to develop his organiza- tion in Albania. He visited Albania personally in 1994, ostensibly as a member of a Saudi “humanitarian organization.”17 Iranian organizations were also quick to move into Albania following the collapse of then Albanian president Sali Berisha’s government in 1997. An Islamic bank was opened in Tirana (in which bin Laden had himself made a financial invest- ment), and in Skadar, the Society of Ayatollah Khomeini was founded.18 As a semblance of normality returned to Albania, however, the new socialist gov- ernment, led by Fatos Nano, assisted the United States in rolling back bin Laden’s network.19 But the eruption of violence in neighboring Kosovo soon provided bin Laden with another opportunity to infiltrate the Balkans.

As the violence in Serbia’s southern province began to increase during the course of 1997, mujahedin located in Bosnia, according to some reports, began to infiltrate Kosovo with the help of the Izetbegovic government. U.S. intelligence officials believed many of the mujahedin who had moved from Bosnia to Kosovo had ties to bin Laden.20 About this time, bin Laden is also reported to have set up terrorist training camps in the northern Albanian town of Tropoje, while some KLA members a group Timothy Garton Ash once described as “a bunch of farmyard Albanian ex-Marxist-Leninist ter- rorists”21—were taken to Afghanistan for training.22 Bin Laden was also at this time reported to have struck a deal with Iran’s Revolutionary Guards to support the KLA’s activities in the hope of turning the region “into their main base for Islamic armed activity in Europe.”23

Despite such public knowledge of the ties between bin Laden and the KLA, in the late 1990s, the United States began actively to support the KLA’s activities. KLA terrorists had hitherto distinguished themselves pri- marily through their control over drug-smuggling routes into Western Europe and their “success” in assassinating refugees, mailmen, and forest rangers in Kosovo. Even the former top American troubleshooter in the Balkans, Robert Gelbard, was claiming in February 1998 that “the KLA is without any question a terrorist group.”24 Yet during the course of 1998, U.S. gov- ernment agencies began arming and training KLA guerrillas in Kosovo, pro- viding them with American military training manuals, field advice, satellite telephones, global-positioning systems, and even the mobile phone number of NATO’s supreme commander, Wesley Clark.25 In short order, the KLA had gone from being a drug-smuggling terrorist group supported by Osama bin Laden to a U.S. ally.

The sad fate of NATO-occupied but KLA-controlled Kosovo is now well known. In 2000, the UN reported that theft, blackmail, and arson had increased 70 percent in the year after NATO took control of the province.26 The flow of drugs through Kosovo has also increased since the Kosovo war, as has Kosovo’s importance as a transit point in the trafficking of women from former Soviet republics to brothels in Western Europe.27 U.S. “allies” such as KLA leaders Hashim Thaci and Agim Ceku are rumored to have been secretly indicted for war crimes by the ICTY.28 And during the NATO- monitored ethnic cleansing of Kosovo, 250,000 Serbs, Roma, Turks, Bosni- acs, and Jews have been forcibly expelled from the province.29

Moreover, bin Laden’s organization in Albania has continued to pose a significant threat to U.S. interests and personnel in the region. The serious- ness of this threat was very much in evidence in June and July 1999, when former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and Secretary of Defense William Cohen were forced to cancel scheduled visits to Albania after it was learned that bin Laden’s operatives in the country were planning assassina- tion attempts on both officials.30

Macedonia and Beyond

After NATO occupied Kosovo, various U.S. agencies initiated a covert cam- paign to foment an insurgency in Albanian-populated villages in southern Serbia as part of an effort to overthrow then-Yugoslav president Slobodan Milosevic. Unfortunately, the American operatives in charge of the clandes- tine Kosovo mission soon lost control over their ostensible KLA allies, and after American interest in the operation dissipated with Milosevic’s over- throw in October 2000, the Albanian guerrillas quickly set their sights on a new target—Macedonia.31 By 27 June 2001, the depth of the failure of America’s alliance with the KLA was painfully apparent when President George W. Bush signed an executive order that, among other things, claimed that several high-ranking KLA members were engaging in actions that “con- stitute an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and for- eign policy of the United States.”32 For their part, Macedonian officials have repeatedly claimed that KLA guerrillas operating in Macedonia have received covert assistance (reportedly up to $7 million) from bin Laden and that a group of mujahedin were currently based near the village of Debra.33

Because NATO has been unable or unwilling to control the Kosovo- Macedonia border, Macedonia is now well on the road to becoming yet another failed Balkan statelet. In the best-case scenario, the political “reforms” that the United States, the European Union, and NATO officials have imposed on the country—strikingly similar to political experiments with a long and established track record of failure in the former Yugoslavia and in Bosnia-Herzegovina—will guarantee that Macedonia becomes another dysfunctional Balkan state with an unworkable constitution and a politically and ethnically polarized population. In the worst-case scenario, the current “cease-fire” will provide only a brief respite before a full-scale resumption of the conflict.

The United States and the NATO alliance now confront a situation in the Balkans they have in large measure helped to create. Yet as their diplomatic energies and military and intelligence resources are of necessity shifted fur- ther east, the attention given the Balkans over the past decade will dimin- ish. Such a change, however, will produce considerable dangers. As seen above, members of al Qaeda apparently believe that the Balkans are now a safe place for them to lie low while Western pressure is focused on Afghanistan. But as is clear from the cases of Bosnia, Kosovo, and Macedo- nia, the U.S. inclination to tolerate the presence of such groups in southeast- ern Europe has serious repercussions for the region—and for the United States as well.

Gordon N. Bardos is the assistant director of the Harriman Institute at Columbia University.

-

See, for instance, Hugh Williamson, “Al Qaeda Group Has Strong German Support Network,” Financial Times (London), 27 September 2001.

-

For analyses of Islamic traditions and practice in southeastern Europe, see H. T. Norris, Islam in the Balkans: Religion and Society between Europe and the Arab World (London: Hurst and Company, 1991); Hugh Poulton and Suha Taji-Farouki, eds., Muslim Identity and the Balkan State (London: Hurst and Company, 1997); Tone Bringa, Being Muslim the Bosnian Way: Identity and Community in a Central Bosnian Village (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1995); Ger Duijzings, Reli- gion and the Politics of Identity in Kosovo (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000).

-

Though commonly referred to as “Bosnian Muslims” in the Western press, since 1993 the Bosnian Muslims have adopted the term Bosniac to identify themselves. Bosniac is a more preferable designation given the large number of individuals in Bosnia who are of Muslim background but are athe- ists and consequently prefer to use a term that does not have religious connotations.

-

Many of these ties are outlined in “Iran’s European Springboard?” a report by the U.S. House of Representatives’ Task Force on Terrorism and Unconventional Warfare, Washington, D.C., 1 Septem- ber 1992.

-

Alija Izetbegovic, Islamska Deklaracija (Sarajevo: Osna, 1990), 22–43.

-

“Uhapseni generali Alagic i Hadzihasanovic,” Oslobodjenje (Sarajevo), 2 August 2001.

-

John Pomfret, “Bosnian Officials Involved in Arms Trade Tied to Radical States,” and “How Bosnia’s Muslims Dodged Arms Embargo: Relief Agency Brokered Aid From Nations, Radical Groups,” Washington Post, 22 September 1996.

-

Senad Pecanin, “I Osama bin Laden ima bosanski pasos,” Dani (Sarajevo), 24 September 1999. 9. Erich Follath and Günther Latsch, “Der Prinz und die Terror-GMBH,” Der Spiegel, 15 September 2001.

-

“NATO Ministers Agree to Cut Troops in Bosnia,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Newsline, 22 September 1999.

-

“Bin Laden’s Arrested Aide was Bosnian Citizen,” Agence France-Presse, 21 September 1999. The issuance of the Bosnian passport to Amduni was confirmed by then Bosnian deputy minister for civilian affairs and communications, Nudzeim Recica.

-

New York Times, 26 June 1997, “News Summary” section.

-

Jeffrey Goldberg, “Learning How to Be King,” New York Times Magazine, 6 February 2000.

-

“Na Ilidzi uhapsena trojica Bin Ladenovih saradnika,” Oslobodjenje, 25 July 2001.

-

Carlotta Gall, “NATO Says Four Were Seized Near Sarajevo, Suspected of Terror Activities,” New York Times, 2 October 2001.

-

“Bosnian Leadership Prepared to Intercept Militants with Links to bin Laden,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Newsline, 1 October 2001.

-

Simon Reeve, The New Jackals (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1999), 180.

-

Tom Walker, “US Alarmed as Mujahedin Join Kosovo Rebels,” Times (London), 26 November 1998; Steve Rodan, “Kosovo Seen as New Islamic Bastion,” Jerusalem Post, 14 September 1998.

-

“Prospects Dwindle for Withdrawal of U.S. Troops from Balkans,” Stratfor, 2 February 2001.

-

Rodan.

-

See Timothy Garton Ash, “Kosovo: Was It Worth It?” New York Review of Books, 21 September 2001, 53.

-

“KLA Rebels Train in Terrorist Camps,” Washington Times, 4 May 1999. See also Chris Hedges, “Kosovo’s Next Masters?” Foreign Affairs 78 (May/June 1999), 39.

-

Uzi Mahnaimi, “Iranians Move In,” Sunday Times (London), 22 March 1998.

-

Hedges, “Kosovo’s Next Masters?” 36.

-

Tom Walker and Aidan Laverty, “CIA Aided Kosovo Guerrilla Army,” Times (London), 12 March 2000.

-

Nehat Islami, “Kosovo Crime Wave,” Balkan Crisis Report (Institute for War and Peace Report- ing), 17 January 2000.

-

Maggie O’Kane, “Kosovo Drug Mafia Supply Heroin to Europe,” Guardian Unlimited, 13 March 2000.

-

Tom Walker, “KLA Faces Trials for War Crimes on Serbs: Inquiry Turns on Albanians,” Sunday Times (London), 3 September 2000; Chris Hedges, “Kosovo’s Rebels Accused of Executions in the Ranks,” New York Times, 25 June 1999.

-

“Refugee Cycle Threatens Balkan Stability,” Reuters, 20 March 2000.

-

“Security Concerns Forced Albright to Cancel Albania Trip,” CNN Headline News, 16 July 1999, available at www.cnn.com; “Pentagon Chief Cancels Albania Visit over Terrorist Threat,” CNN Head- line News, 15 July 1999, available at www.cnn.com.

-

Peter Beaumont, Ed Vulliamy, and Paul Beaver, “CIA’s Bastard Army Ran Riot in Balkans- Backed Extremists,” Observer, 11 March 2001.

-

“Executive Order Blocking Property of Persons Who Threaten International Stabilization Efforts in the Western Balkans,” Washington, D.C., White House, 27 June 2001. See also “UN Suspends Five Top Members of Kosovo Civil Corps,” Agence France-Presse, 6 July 2001.

-

D. Joksic, “Albanci nisu povezani sa Bin Ladenom,” Oslobodjenje, 24 September 2001.