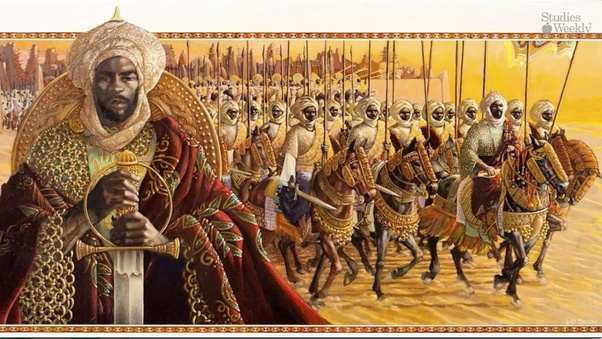

The Spanish occupation by the Moors began in 711 AD when an African army, under their leader Tariq ibn-Ziyad, crossed the Strait of Gibraltar from northern Africa and invaded the Iberian peninsula “Andalus” when Spain was under the Visigoths rules.

The Spanish occupation by the Moors began in 711 AD when an African army, under their leader Tariq ibn-Ziyad, crossed the Strait of Gibraltar from northern Africa and invaded the Iberian peninsula “Andalus” when Spain was under the Visigoths rules.

The existence of a Muslim kingdom in Medieval Spain where different races and religions lived harmoniously in multicultural tolerance is one of today’s most widespread myths. University professors teach it. Journalists repeat it. Tourists visiting the Alhambra accept it. It has reached the editorial pages of the Wall Street Journal, which sings the virtues of the “pan-confessional humanism” of Andalusian Spain (July 18, 2003).

The Economist echoes the belief: “Muslim rulers of the past were far more tolerant of people of other faiths than were Catholic ones. For example, al-Andalus’s multi-cultural, multi-religious states ruled by Muslims gave way to a Christian regime that was grossly intolerant even of dissident Christians, and that offered Jews and Muslims a choice only between being forcibly converted and being expelled (or worse).” The problem with this belief is that it is historically unfounded, a myth. The fascinating cultural achievements of Islamic Spain cannot obscure the fact that it was never an example of peaceful convivencia.

The history of Islamic Spain begins, of course, with violent conquest. Helped by internal dissension among the Visigoths, in 711 A.D. Islamic warriors entered Christian Spain and defeated the Visigothic king Rodrigo. These Muslims were a mixture of North African Berbers, or “Moors,” who made up the majority, and Syrians, all led by a small number of Arabs proper (from the Arabian peninsula). The Crónica Bizantina of 741 A.D., the Crónica mozárabe of 754 A.D. and the illustrations to the thirteenth-century Cantigas de Santa María chronicle the brutality with which the Muslims subjugated the Catholic population. From then on, the best rulers of al- Andalus were autocrats who through brute force kept the peace in the face of religious, dynastic, racial, and other divisions.

These divisions, and the ruthless methods of dealing with them, were not unique to Muslim Spain. The jihad launched around 634 against the then-Christian Middle East by the successors of Muhammad was marked by internal conflict after the assassination of the third Caliph, Uthman (644-656). The founder of the Emirate of Cordoba, Abd al-Rahman I (734?-788), “The Emigrant,” had to flee Syria to avoid the extermination ordered against his Umayyad family by the rival Abassids.

Allied with Berbers from North Africa and helped by Yemenite and Syriansettlers in Spain willing to betray their masters, he proceeded to enter Spain from Africa, defeat the governor of al- Andalus in 756, and make himself Emir. He kept peace among Muslims and between Muslims, Catholics, and Jews by means of an army of more than 40,000 soldiers. It was he who ordered the demolition of the ancient Catholic church of Cordoba to build the much admired mosque. During his reign and that of Abd al-Rahman II (822-852), the conqueror of Barcelona, Catholics suffered confiscations of property, enslavement, and increases in their exacted tribute, which helped finance the embellishment of Islamic Cordoba.

Under Abd al-Rahman II and Muhammad I (822-886), a number of Catholics were killed in Cordoba for preaching against Islam, while others were expelled from the city. Among these victims was Saint Eulogio, beheaded by the Islamic authorities. Muhammad I ordered that “newly constructed churches be destroyed as well as anything in the way of refinements that might adorn the old churches added since the Arab conquest.”

Abd al-Rahman III (912-961), “The Servant of the Merciful,” declared himself Caliph of Cordoba. He took the city to heights of splendor not seen since the days of Harunal- Rashid’s Baghdad, financed largely through the taxation of Catholics and Jews and the booty and tribute obtained in military incursions against Catholic lands.

He also punished Muslim rebellions mercilessly, thereby keeping the lid on the boiling cauldron that was multicultural al- Andalus. His rule presumably marks the zenith of Islamic tolerance. Al-Mansur (d. 1002), “The One Made Victorious by Allah,” implemented in al-Andalus in 978 a ferocious military dictatorship backed by a huge army. In addition to building more palaces and subsidizing the arts and sciences in Cordoba, he burned heretical booksand terrorized Catholics, sacking Zaragoza, Osma, Zamora, Leon, Astorga, Coimbra, and Santiago de Compostela. In 985 he burned down Barcelona, enslaving all those he did not kill.

By 1031 the internal divisions of al- Andalus had caused its fragmentation into several tyrannical little “kingdoms,” the socalled taifas.

Between 1086 and 1212, new waves of Islamic jihadists from North Africa washed over the land. The first wave were the almoravides, fundamentalist warriors invited by the taifa rulers to help them against the growing strength of the Catholic kingdoms.

With the support of the Muslim Andalusian masses and of Muslim legal scholars, who resented the heavy taxation and what they regarded as the debauched and impious life of their princely rulers, the almoravides deposed the taifa kings and unified Andalusia.

They pushed back the Catholic advances and made the life of both Catholics and Jews much more difficult than before. By 1138, however, their empire was falling apart under pressure from the Catholic kingdoms and another wave of North African fundamentalist Muslims, the almohades. The almohades thought that the almoravides had become too lax in their practice of Islam—perhaps, one may surmise, because of contagion from the Catholics.

By 1170 the almohades had taken control of Andalusia and unleashed new horrors on Catholics, Jews, and other Muslims. That the ruthless almohades also produced marvelous architecture and were responsible for the beauty of some mozarabic buildings, such as Santa María la Blanca in Toledo, captures nicely the true nature of Andalusian Spain. But the almohades were decisively beaten by the allied kings of Castile, Aragon, and Navarra at Navas de Tolosa in 1212. From then on the Catholics kept the military initiative, finally defeating the last Muslim kingdom, Granada, in 1492.

The early Muslim invaders were relatively small in numbers, so it was politically prudent to grant religious autonomy to Catholics, while trying to protect themselves from the “contagion” of Catholic influence by segregating themselves from the subject majority. Therefore they maintained the Catholics in a state of dhimmitude —as a “protected” class curtailed from any possibility of sharing political power or compromising the hegemonic position of Islam. In times of war or political turmoil, the Catholics’ freedom was further restricted. Catholics fleeing Muslim rule lost all “protection,” and their property was confiscated by the conquerors. “Tolerance at this extreme,” notices historian Robert I. Burns, “is not easily distinguished from intolerance.”

For similar reasons of strategy, not “tolerance,” the invaders obtained the help of Jewish leaders unhappy with their treatment under the Visigoths. Contrary to popular opinion, Jews were not very numerous, either in Andalusia or in Catholic Spain, but for a time Jewish garrisons kept an eye on Catholics populations in key cities like Cordoba, Granada, and Toledo. Jewish leaders achieved positions of power, as visirs (prime ministers), bankers, and counselors. Others wrote brilliant literary works, mostly in Arabic. Jews thus formed for a time an intermediary class between the hegemonic Muslims and the defeated Catholics. This was the so-called “Spanish Jewish Golden Age.” But Jews remained dhimmi, a group subject to and serving the Muslim rulers.

These presumably “best of times” ended in any event with the arrival of the jihadist almoravides and almohades. Jews as well as Catholics fell victim to their religious zeal. Many Jews migrated to Catholic lands, where some became important writers (the author of the Zohar) and men of influence (diplomats, bankers, tax collectors, finance ministers to kings). They participated in the achievements of the reign of Alfonso X “The Learned” of Leon and Castile (1221- 1284), who gathered in Toledo speakers of many languages and ordered the translation of Arabic moral works such as the Calila e Dimna along with the production of Spanish scientific, legal, and historical treatises, and who himself wrote lyric poems in Spanish and a classic of Galician literature, the Cantigas de Santa María.

Upon conversion, some members of formerly Jewish families (conversos) reached important positions within the government (the wealthy Luis de Santangel, tax collector and financial officer to Ferdinand and Isabella, and Gabriel Sanchez, treasurer of the kingdom of Aragon) and the church (bishop Pablo de Santa María, and Tomás de Torquemada), and even intermarried with the nobility.

They also suffered periodic bloody persecutions at the hands of peasants and the urban lower classes while being generally protected by the upper nobility and the higher echelons of the church, in a way reminiscent of Islamic “protection.”

This pattern had been evident under Muslim rule as well: in Granada in 1066—before the arrival of the almoravides—rioting Muslim mobs assassinated the rabbi and visir Joseph Ibn Naghrela and destroyed the entire Jewish community; thousands perished—more than those killed by mobs in the Rhineland at the beginning of the First Crusade.

Commenting on these events, the memoirs of king Abd Allah of Granada (c. 1090) muster familiar anti-Jewish accusations against the visir: avarice, deception, treason, and favoritism toward coreligionists.

Muslim suspicion of the Jewish community lasted until the end of Islamic rule: before surrendering Granada to Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492, Muslims inserted a clause in the peace treaty protecting themselves fromfeared Jewish hegemony: “their Highnesses [the Catholic monarchs] will not allow Jews to lord or be tax collectors over Moors.”

“The Golden Age of equal rights was a myth,” writes historian Bernard Lewis, “and belief in it was a result, more than a cause, of Jewish sympathy for Islam.” Nevertheless, some writers continue to insist that “Jews lived happily and productively in Spain for hundreds of years before the Inquisition and the Expulsion of 1492.”

Let us then consider more closely the evidence for the supposed Andalusian multicultural harmony. This enlightened state presumably culminated under the exemplary reign of Abd-al-Rahman III, “The Servant of the Merciful” (912-961).

The admiring words of the contemporary Muslim historian Ibn Hayyan, however, reveal a different picture: Abd-al-Rahman III, we are told, kept Islam safe from religious dissension, “saving us from the trouble of having to think for ourselves”; under him “the people were one, obedient, quiet, submissive, not self-sufficient, governed rather than governing”; he succeeded by applying religious inquisition efficiently, “persecuting factions by all means available…chastising the innovations of those who drifted away from the views of the community.”

This tenth-century ruler, long before the almoravids and almohads, was as effective as he was at maintaining control, thanks to the thoroughness so admired by his chronicler, which included the exhumation of the muladí (a Muslim of partly or wholly Catholic ancestry) rebel Omar ben Hafsun and his son—in order to prove that both had died as Catholics and thus justify the public desecration of their bodies. With the money collected from the taxation of Catholics and Jews and from the booty and tribute obtained through military incursions into Catholic lands, Abd-al-Rahman III not onlyembellished Cordoba, but built for his favorite female slave a splendid palace, Medina-Zahara. It contained 300 baths, 400 horses, 15,000 eunuchs and servants, and a harem—not a Catholic institution— of 6,300 women. In 1010 the Berbers destroyed the palace in the course of their jihad and knifed all its occupants.

In the eleventh century, again before the invasion of almoravides and almohades, the man of letters Ibn Hazm saw his books burned and was imprisoned several times. And long after almoravid and almohad rule, the fourteenth-century thinker Ibn al-Jatib was persecuted, exiled to Morocco, and assassinated in prison. Indeed, already in the first century after the conquest, the malikite way of Islam “configured a closed society in which alfaquis, muftis, and cadis exercised an iron control over the Muslim and non-Muslim population.”

No wonder that when political correctness did not yet exist, the great historian of Islam Evariste Lévi-Provençal observed: “The Muslim Andalusian state appears from its earliest origins as the defender and champion of a jealous orthodoxy, more and more ossified in a blind respect for a rigid doctrine, suspecting and condemning in advance the least effort of rational speculation.”

Of course, such official injunctions were not always obeyed. But laxity of enforcement was not unique to Andalusia. It has existed also in other societies, most often for the powerful or rich. As Ibn Abdun again wisely writes, “No one will be absolved because of a transgression against religious law, except in the case of people of high social position, who will be treated accordingly, as the Hadith stipulates: ‘Forgive those in elevated social position,’ since for them corporal punishment is more painful.”

Let us next examine racial tolerance. The Quran does not proclaim the innate superiority of any racial group. But the enslavement of black Africans was an entrenched part of the culture of Andalusia. So was racial prejudice. In his Proverbs, al-Maydani (d. 1124) wrote, “the African black, when hungry, steals; and when sated, he fornicates.”

Traveling through Africa, Ibn Battuta (1207-1377?) claimed that blacks were stupid, ignorant, cowardly, and infantile. These attitudes could be found throughout the Islamic world. Early in the wonderful Arabian Nights, the worst thing about the adultery of the wives of kings Sahzman and his brother Shariyar is that their infidelity was with blacks. In Nights 468, a black slave is rewarded for his goodness by being transformed into a white man. A similar case occurs in the eleventhcentury “Epistle of the Pardon” by al- Ma’arri, where a black woman, because of her good behavior, ends up as a white huri in Paradise.

In 1068, before the arrival of the almoravids, the cadi of Muslim Toledo, the Arab Sa’id Ibn Ahmadi, wrote a book classifying the nations of the world. In it he accounted the inhabitants of the extreme North and South as barbarians, describing Europeans as white and mentally deficient because of undercooking by the sun, and Africans as black, stupid, and violent because of overcooking. In contrast, Arabs were done just right. Racial self-consciousness led the Andalusian Ibn Hazm to insist that the Prophet Muhammad, his family, and his predecessors, were all white and ruddy-skinned.

What about the claim regarding the “progressive” status of women in Andalusia? Muslim treatises tell a different story. Ibn Abdun lists numerous rules for female behavior in everyday life: “boat trips of women with men on the Guadalquivir must be suppressed”; “one must forbid women to wash clothes on the fields, because the fields will turn into brothels. Women must not sit on the river shore in the summer, when men do”; “one must especially watch out for women, since error is most common among them.” Elsewhere he also condemns wine drinking, gambling, and homosexuality, following the Quran and the Hadith.22 Truly “liberated” women like the now much admired Wallada bint al-Mustafki (994-1091) were exceptions.

The average woman inAndalusia was treated much the same as elsewhere under Islamic sharia, with practices like wearing the hijab (following Quran S. xxxiii. 59), separation from men, confinement to the household, and other limitations that did not exist in Catholic lands. Even the much praised poetry of El collar de la paloma displays attitudes that would be called misogynistic today.

What misleads some observers is a phenomenon occurring in many societies: on the one hand, men treat their wives, sisters, and daughters as worthy of respect in certain ways the men consider well-intentioned, which may include sheltering them in the house, keeping them away from opportunities to have sex outside accepted channels, or even hiding their faces and the contours of their bodies; on the other hand, the same men grant much “freedom” to women they do not consider worthy of respect, such as dancers, singers, concubines, mistresses, slaves, or prostitutes, who may display greater “knowledge” and “intellectual sophistication” than their more respected sisters.

This was the case, for example, in ancient Greece, where Pericles could have his mistress, the hetaira Aspasia, participate in areas of public life unthinkable for a proper Greek wife, sister, or daughter. Yet no one speaks of the remarkable freedom granted by ancient Greece to its women. This difference in treatment was in fact noticed by Muslim writers, such as al- Yahiz in the ninth-century Middle East; and after three hundred years, the great Andalusian philosopher Averroes observed that things had not changed: the lives of free women, he noticed, were plant-like, revolving around birthing and caring for the family.23 Averroes deplored the situation, but such disagreements were precisely what contributed to his persecution and eventual banishment from al-Andalus.

The justly celebrated artistic achievements of Islamic Spain suffer from relatedlimitations. The lack of a central authority in Sunni Islam, the ruling form in al- Andalus, has allowed clerics a range of interpretation that runs from looking down upon certain activities to rejecting them altogether. Thus, artistic representations of Muhammad and of the human form in general have been almost unanimously rejected throughout Islam—although one finds exceptions in some countries at some point or another, for example in Persia and Turkey. This fundamental prohibition has curtailed the artistic range of Islam, with the human body finding no representation and painting confined to abstract lines and curves.

An even greater problem exists with music. Islam does not forbid the creation of music. And again, greater freedom has been enjoyed by the powerful and the wealthy, who could at times patronize musicians and singers who in al-Andalus pleased rich and poor alike. But the dominant religious position has been to impede the existence of music as much as possible.

Malik ben Anas (713-795), founder of the Sunni malikite Islamic “way,” to which a majority of Andalusian Muslims belonged, considered music an enemy of piety. Hence Ibn Abdun: “musicians must be suppressed, and, if this cannot be done, at least they must be stopped from playing unless they get permission from the cadi.”

Even today, some Islamic ascetics forbid the use of music in religious acts. In fact, the music one hears in mosques does not go beyond the sound of tambourines, an instrument not conducive to the creation of great musical scores. The curious result was that, in Andalusia, the best “Arabic” music turns out to be mozarabic— that is, the music of Catholics under Muslim domination: Catholics could and did adapt “Muslim” sounds to a religious ritual—the Mass—which had no problems with using music for spiritual purposes and which as a result has produced impressive orchestral and choral compositions.

Similarly, other violations of Muslim practices (such as the prohibition on drinking wine) by the powerful of Andalusia, often pointed out as proof of the unique tolerance of Muslim Spain, resulted from the corrupting influence of Catholics, who drank wine liberally. Such exceptions were not unique to Andalusia.

They can also be found in other Muslim communities along the Mediterranean where historic Catholic influence has remained relatively strong, such as Tunisia. The influence of non-Muslim civilizations may account also for other deviations from orthodoxy, not only in Andalusia, but in places like Persia (Iran) and India. The risqué quality of many tales in the Arabian Nights may well trace its origin to the pre-Muslim Persians and even the Christian Byzantines. The Muslim poet Omar Khayyam sang the beauties of wine, song, and sex, but he was Persian. Another instance is the Andalusian poet Ibn Quzman, much praised today for his singing of eroticism and homosexuality: his admirers overlook that he was blond and blue-eyed, and that these facts, together with a name like Ibn Quzman (Guzmán or Guttman), mean that he was of Hispanic (indeed Visigothic, that is, Germanic) origin.

In fairness to Islam, it must be said that convivencia was not furthered by the other two religious groups of al-Andalus either. The Catholic lower classes did not harbor much good will toward Muslims, Jews, or those of their own who converted to Islam— whom they called “renegades.”

Their position on the Andalusian totem pole prevented their acting on these feelings, which they at times vented amply in Catholic lands; but in Andalusia Catholics were an integral part of a multicultural social system characterized by “group isolation, superficial contacts, and reciprocal hatreds.”

True, the Quran claims that Christians are dearer to Muslims than are Jews (S. v. 82), but this theoretical advantage was not of much help in practice. Catholics even suffered mass deportations: at the beginning of the twelfth-century, Muslims expelled the Catholics (mozarabs) of Malaga and Granada en masse to Morocco. Muslims rarely authorized the building of new churches, the repair of old ones, or the tolling of bells. In twelfth century Granada, Muslims destroyed the entire Catholic population. Even the muladies, unhappy with their inferior status, revolted against their rulers (cf. Omar ben Hafsun), while the mozarabs also resented their condition and occasionally colluded with their brethren in the Catholic kingdoms.

The Spanish Jewish community was not much more harmonious, perhaps because of “contagion” from the zeal of Spanish Muslims and Catholics.

The autonomy granted by their dhimmi status in Andalusia may also have favored intolerance. In Granada, rabbi and visir Ibn Naghrela “The Prince” boasted that “[Andalusian] Jews were free of heresy, except for a few towns near Christian kingdoms, where there is suspicion that some heretics live in secret. Our predecessors have flogged a part of those who deserved to be flogged, and they have died from flogging.”

In Catholic lands in the eleventh century, Orthodox Jews persecuted the then thriving Karaite Jewish community, which rejected the authority of the Talmud, and expelled it. Spanish Jewish literature was not averse to showing hostility towards Muslims and Catholics: Abraham bar Hiyya (d. c. 1136) concentrated on the Catholics, while the Cancionero of Antón de Montoro preferred to satirize the mudéjares.

Both the Muslims and the Catholics were treated harshly in some of the works of the Andalusian Talmudic commentator and philosopher Moses Maimonides (1135-1204). His views could have been affected by his unhappy experiences: the almohades’ enforced conversions caused Maimonides and his family to escape first to the Catholic kingdoms and later to Morocco and Egypt. No wonder that in a letter to Jewish Yemenites he wrote that no “nation” compared to Islam in the damage and humiliation it had inflicted on “Israel.”

By any objective standards, then, and in spite of its undeniable artistic, literary, and scientific accomplishments, and of modern wishful “let-us-all-get-along” thinking that tries to gloss over evidence to the contrary, Islamic Spain was not a model of multicultural harmony. Andalusia was beset by religious, political, and racial conflicts controlled in the best of times only by the application of tyrannical force. Its achievements are inseparable from its turmoil.

How then can one explain the persistence of the belief that Andalusia was a land of peaceful coexistence? The historian Richard Fletcher has attempted one possible explanation: “[In] the cultural conditions that prevail in the West today the past has to be marketed, and to be successfully marketed it has to be attractively packaged. Medieval Spain in a state of nature lacks wide appeal. Self-indulgent fantasies of glamour…do wonders for sharpening up its image. But Moorish Spain was not a tolerant and enlightened society even in its most cultivated epoch.”

Another explanation could be what one might call Spanish self-hatred, the obverse of what once was Spanish self-aggrandizement. Such a view allies itself effortlessly with many non-Spaniards’ hatred of CatholicSpain, in an attitude that sooner or later brings up Las Casas’ condemnation of the Spanish conquest of the Americas—while ignoring the question of why there was not an English, Dutch, or French Las Casas to criticize the English, the French, and the Dutch. As if these nations carried out conquests that left undisturbed the native populations of their colonial lands.

A more convincing explanation may be that extolling al-Andalus offers the double advantage of surreptitiously favoring multiculturalism and deprecating Christianity, which is one of the foundations of Western civilization. This mechanism is not unlike that in the mind of those who dislike Western culture intensely, but who with the fall of Communism find themselves without any clear alternative and so grab Islam as a castaway grabs anything that floats. So anyone who dislikes Western culture or Christianity—for any reason, be it religious, political, or cultural—goes on happily pointing out, regardless of the facts, how bad Catholic Spain was when compared to the Muslim paradise.

SOURCE:

- Fernández Morera: “The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise: Muslims, Christians, and Jews Under Islamic Rule in Medieval Spain”. ISI Books, 2016. ISBN-13: 978-1610170956