In Bosnia and Herzegovina, each of the three constituent peoples (Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croats) has its own education program. There are multiple publishers on the market, and schools, or rather teachers, independently choose which textbooks to use. For an analysis of the Bosniak perspective on history, we selected textbooks published by Sarajevo Publishing. National (Bosniak) history is taught in textbooks from grades 6 to 9 in primary school and in textbooks for high schools, specifically from the 2nd to the 4th grade.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, each of the three constituent peoples (Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croats) has its own education program. There are multiple publishers on the market, and schools, or rather teachers, independently choose which textbooks to use. For an analysis of the Bosniak perspective on history, we selected textbooks published by Sarajevo Publishing. National (Bosniak) history is taught in textbooks from grades 6 to 9 in primary school and in textbooks for high schools, specifically from the 2nd to the 4th grade.

Middle Ages

Regarding the Middle Ages, the history of Europe, Byzantium, and the Arab world (the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties) and the emergence of Islam are covered. The textbook with a historical reader for the second year of high school (authors Esad Kurtović and Samir Hajrulahović), in the lesson “The Slavs and their Civilizational Framework,” analyzes religion, language, and script. It is stated that South Slavic languages include Slovenian, Croatian, Serbian, Bosnian, Montenegrin, Macedonian, and Bulgarian.

“The oldest scripts are Glagolitic and Cyrillic…” The origins of these scripts are explained, and the first states of the South Slavs are listed.

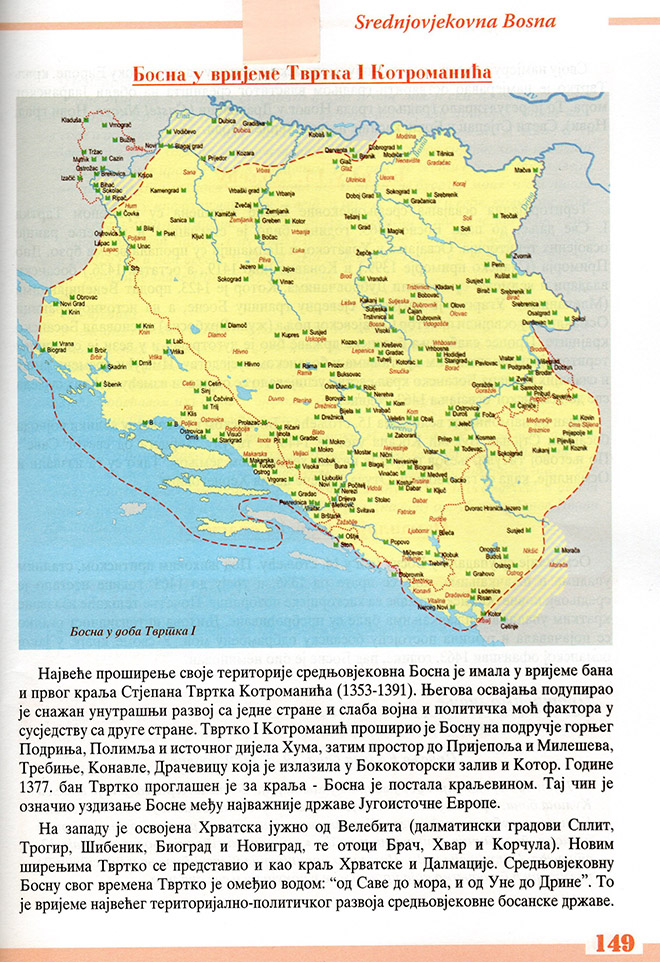

“In Southeast Europe, among the South Slavs, Karantania (in the territory of Slovenia and Austria), Croatia during the Trpimirović dynasty, Serbia during the Nemanjić dynasty (particularly Dušan’s empire), Duklja (later Zeta), Samuil’s empire (Macedonia), the Bulgarian empire, and the Kingdom of Bosnia (notably during the reign of Tvrtko I Kotromanić) stand out.”

Kingdom of Bosnia

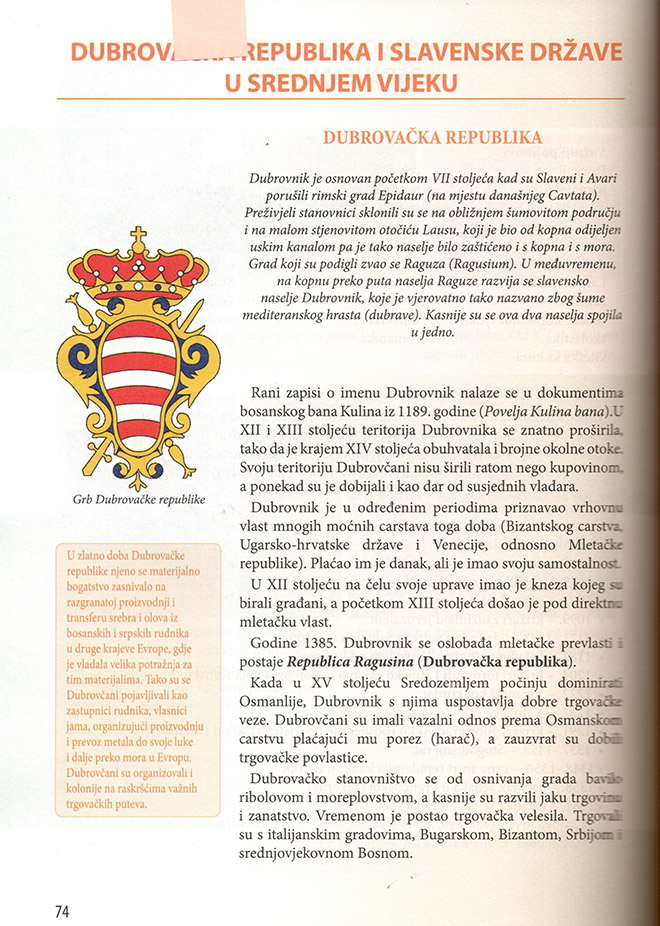

In the 7th-grade textbook, the Pacta Conventa (the agreement between Croats and Hungary) from 1102 and a text about Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus containing information about Croats are included. Two pages are dedicated to the Republic of Dubrovnik.

In the 7th-grade textbook, the Pacta Conventa (the agreement between Croats and Hungary) from 1102 and a text about Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus containing information about Croats are included. Two pages are dedicated to the Republic of Dubrovnik.

In the textbook for the 2nd grade of high school, medieval Bosnia is positioned between East and West.

“The religious landscape of medieval Bosnia was marked by the presence of Catholicism, Orthodoxy, and the Bosnian Church. Preserved written monuments indicate the presence of Glagolitic, Cyrillic (Bosančica), and Latin scripts, as well as the Bosnian and Latin languages in public and everyday administration.” A separate chapter focuses on the territorial-political development of medieval Bosnia.

“By the end of the 13th and the beginning of the 14th century, it was under strong influence from the Bribir princes (Šubić family), who exercised their authority in the Croatian region in conflicts with the Hungarian king, and with their decline, Bosnia experienced a rapid rise. During the reign of Ban Stjepan II Kotromanić (1322–1353), Bosnia expanded to the western part of Hum and Dalmatia, from the Cetina to Dubrovnik.”

Territorial Expansion of Bosnia

Pavao Šubić (1245–1312) was an uncrowned king of Croatia, “Ban of the Croats and Lord of Bosnia.” His brother Mladen I and son Mladen II were Bosnian bans from 1299 to 1320, and Mladen II was “Ban of the Croats and Bosnia” and “Lord of the entire Hum land.” Pavao Šubić’s granddaughter, Jelena Šubić Bribirska (1338–1378), was the wife of nobleman and Ban Stjepan Vladislav Kotromanić (1295–1354) and the mother of future King Tvrtko. None of this is mentioned in the textbooks.

The territorial expansion of Bosnia culminated with Ban and first King Stjepan Tvrtko I Kotromanić (1353–1391), while conquests in Croatia and Dalmatia were merely episodic.

“Part of the Primorje (Slansko Primorje in 1399) and Konavle (part in 1419 and the rest in 1426) were sold to the Dubrovnik citizens by Bosnian rulers and magnates.”

Stjepan Vukčić Kosača, one of the greatest noblemen of the Bosnian Kingdom, adopted the title “Duke of St. Sava” in 1448, giving Herzegovina its name.

In the lesson “Bosnia and its Neighbors during the Middle Ages,” it is noted how the Croatian state developed under the Trpimirović dynasty.

“During the early Middle Ages, Bosnia was occasionally part of the Croatian state. In its development, Bosnia expanded southwestward and northwestward into areas that were part of the Croatian state. Overall, Croatia, as Bosnia’s western neighbor in the Middle Ages, developed and transferred to Bosnia, in addition to its own achievements, the broader accomplishments of Western European, Mediterranean, and medieval culture infused with Catholicism.”

Dubrovnik and Bosnian Church

A significant portion is dedicated to Dubrovnik’s development, with a photograph of the city included. A description of Dubrovnik’s political structure, as written by Filip de Diversis, is also provided.

A significant portion is dedicated to Dubrovnik’s development, with a photograph of the city included. A description of Dubrovnik’s political structure, as written by Filip de Diversis, is also provided.

However, Bosniak (Muslim) textbooks in Bosnia and Herzegovina focus heavily on one Christian church—the Bosnian Church. The intent is to establish that today’s Bosniak Muslims are descendants of Bosnian Church members.

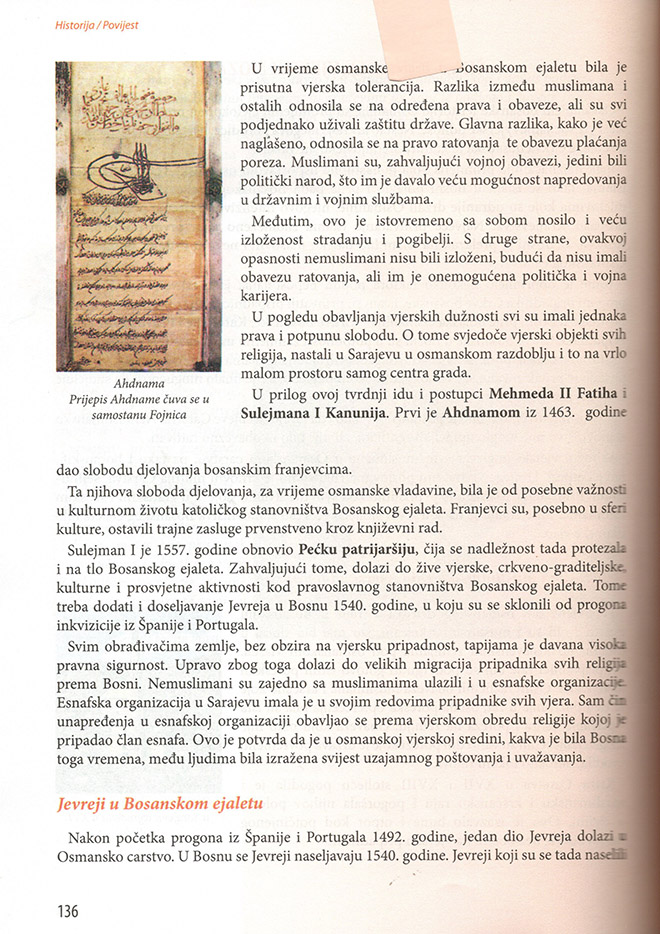

Authors across all Bosniak (Muslim) textbooks promote the thesis that the “Krstjani” accepted Islam willingly. There is no mention of Islam being imposed by fire and sword.

In the textbook for the 2nd year of high school (authors Esad Kurtović and Samir Hajrulahović), the Bosnian Church is defined as favored by nobles and Bosnian rulers.

“Among public authorities in Bosnia, particularly the ruling feudal lords and rulers, the Bosnian Church was privileged as a protector of the order.”

The basis for this statement remains unclear. The textbook is filled with contradictions.

The textbook also examines the crisis of the Catholic Church in Bosnia, the failure of Dominican missionaries, and the success of Franciscans.

“In Bosnia, Franciscans achieved better positions for Catholicism than the Bosnian bishopric from Đakovo. With Franciscan presence and action, the Bosnian Church gained a strong competitor. Catholicism eventually assumed the dominant position in Bosnia once held by the Bosnian Church.”

Thus, it is concluded that it was not the Bosnian Church but Catholicism that was privileged as the protector of the order. Didn’t Ban Kulin declare his Catholicism and orthodoxy publicly at Bilino Polje in the presence of Pope Innocent III’s legate John de Casamaris? Yet, the authors, in creating a new narrative of Bosnian history, reinterpret the assembly at Bilino Polje differently.

Bosnian Queen Katarina

The story of the last Bosnian queen, Katarina, is told over three pages in the textbook.

The story of the last Bosnian queen, Katarina, is told over three pages in the textbook.

Katarina, the daughter of Stjepan Vukčić Kosača and Jelena Balšić, married King Stjepan Tomaš (1443–1461).

“The Ottoman advance into Bosnia in 1463 led to Katarina seeking refuge in Dubrovnik, as well as the capture of her children.”

The authors neglect to state that the queen did not “seek refuge” but rather fled for her life. In the ensuing chaos, her children were captured and taken to Istanbul, where they were forcibly converted to Islam.

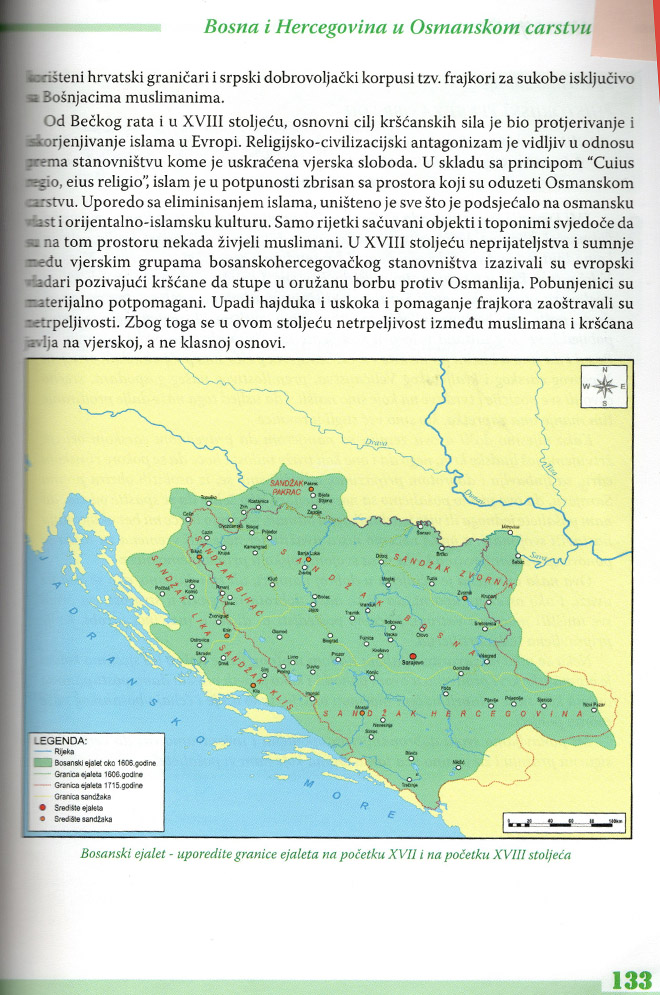

After the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699, the Ottomans lost large territories in Croatia and Hungary. Here is how the losses of the Ottomans are described in the high school textbook:

After the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699, the Ottomans lost large territories in Croatia and Hungary. Here is how the losses of the Ottomans are described in the high school textbook: